Why redesigning our primaries could change government for good

Plus: What stage of capitalism is payday loan-themed fast food brand activations, and what does it mean for the midterms?

Why redesigning our primaries could change government for good

What if our political polarization is really a design problem?

In down-ballot elections across the country, voters don’t always have much of a say in who they vote for. The problem is a lack of competition because many districts are “safe” for one party or the other in the general election. That means the primary election, with its lower voter turnout and more partisan electorate, is the only vote that really counts in many races. Redesigning our primary process could help change that.

New research from the Unite America Institute, or UAI, a venture fund that invests in nonpartisan election reform, found just 14% of U.S. voters cast what they call “meaningful votes” in their local U.S. House race, and it’s nominally worse for state legislative races at 13%.

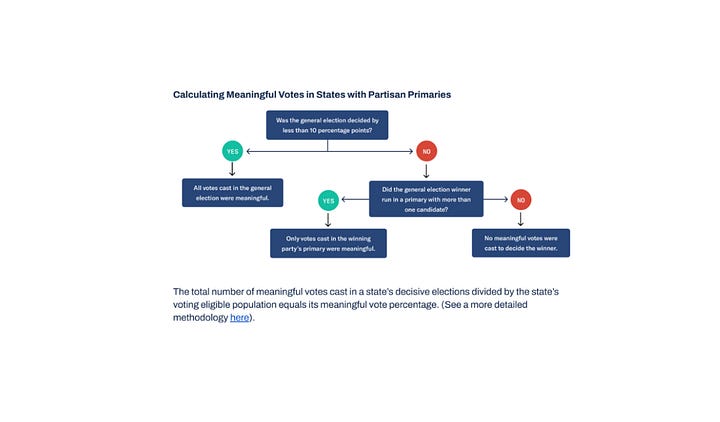

UAI defines a “meaningful” vote by tracking whether a general election is decided by 10 percentage points or less, or that it’s a relatively competitive race. If it’s not, they then looked to see whether the general election winner ran in a primary with more than one candidate (see flow chart below). The total number of meaningful votes cast in each state’s most recent elections from 2022 to 2024 were then divided by the state’s voting eligible population to come up with a percentage.

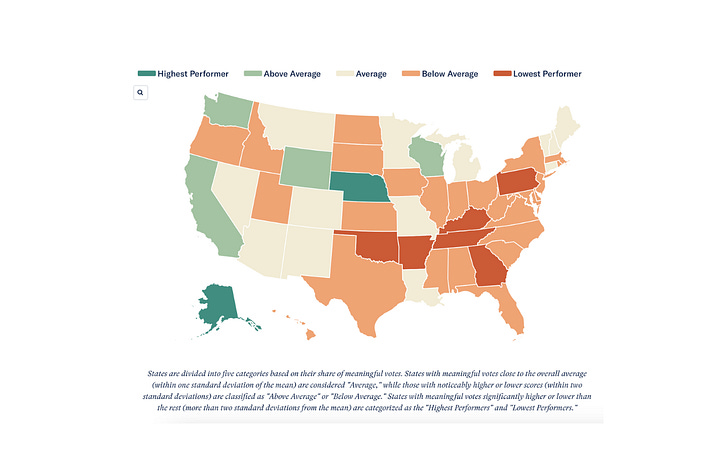

According to this rubric, Nebraska is the top-performing state, with about 37% of its state lawmakers decided by meaningful votes. Congratulations, Cornhuskers.

Nebraska is followed by Alaska at 30%, California at 25%, Wisconsin at 24%, and Wyoming at 21%. Arkansas is the worst performer at 5%, just barely beating out Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, Georgia, and Tennessee at about 6% each. There’s a lot of room for improvement nationwide, and as a result, many of our general elections are a mere formality to elect candidates who already won their primaries.

Making more of our elections competitive and increasing the share of “meaningful” votes is especially pressing considering modern party identification trends. Independent self-identification is at an all-time high at 43%, outnumbering the 28% each of Americans who identify as Democrats or Republicans, according to Gallup. Despite their plurality, independents often find themselves locked out from casting meaningful votes in federal and state legislative races, though. There are 16 states with closed-party primaries where independents or voters not registered to a party can’t vote.

Primary reform could give independents and voters not registered with a party a greater voice, and increasingly states are making that a reality. Last April, New Mexico’s Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham (D) signed a bipartisan bill into law allowing independent voters to vote in state primaries. That might say something about why Democratic gubernatorial candidate and former Interior Secretary Deb Haaland played it so moderate in her announcement video. She needs to win a broad coalition.

But it’s more than just catering to independents. UAI press director Ross Sherman tells me there’s a compelling argument that primary reform could help the major parties too.

“By engaging independent voters earlier in the process, Republicans and Democrats would set themselves up to win the ‘swing vote’ that determines critical general elections,” he says. “It could prevent scenarios like in 2022, when Republicans nominated a bunch of really unpopular Senate candidates in primaries that ended up losing competitive elections in Pennsylvania, Georgia, and elsewhere.”

There are a number of reforms states could take to make their voters’ choices more meaningful, and UAI recommends scrapping party primaries altogether for open-all candidate primaries. There, all candidates regardless of party run in the same primary which is open to all voters, and the top finishers regardless of party advance to the general election. It’s what the top-ranking states of Nebraska, Alaska, and California use, and in theory, it incentives politicians to “govern on behalf of a larger share of voters, not just the tiny minority that currently influences elections,” Sherman says. That’s what happened in Alaska.

Alaska implemented an all-candidate primary in 2022, and since, its share of meaningful votes rose from 21.9% in 2020 to 30% in 2024 and bipartisan government majorities have formed in both its state House and Senate.

“Right now, there’s little incentive for either party to compromise, even when there’s bipartisan agreement across a whole host of issues,” Sherman says, like immigration and climate. “These reforms could help unlock that gridlock.”

Previously in Yello: