The campaign’s hottest design trend is stacked, repetitive typography

Plus: The vice presidential debate made politics brand friendly again

Hello, in this issue we’ll look at…

The campaign’s hottest design trend is stacked, repetitive typography

The vice presidential debate made politics brand friendly again

Scroll to the end to see: who was the best dressed at the debate, according to one men’s fashion magazine 👔

The campaign’s hottest design trend is stacked, repetitive typography

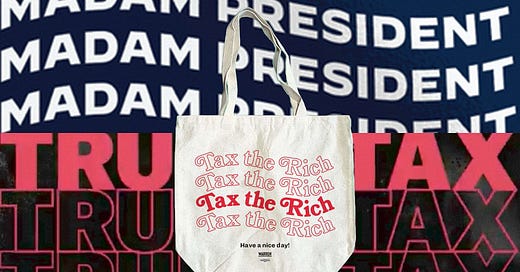

To promote Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s (D-Mass.) call to raise taxes on the ultra-wealthy, her campaign sells “Tax the Rich” merch that repeats the phrase in stacked text across totes, T-shirts, and posters. It’s styled liked a plastic “Thank You” bag, with just one line of text filled in. The rest of the text is outlined. At the bottom it says “Have a nice day!”

In a tutorial for how to make stacked, wavy text, Kettl, a German design software provider, said earlier this year that the style is “making a big comeback” thanks in part to its retro-vintage look. A ban made single-use plastic bags history in New York state, which could say something about a newfound nostalgia for repeating “Thank You”-inspired graphics. Warren’s “Tax the Rich” line was first released in 2022, but its style has since appeared in other campaigns too.

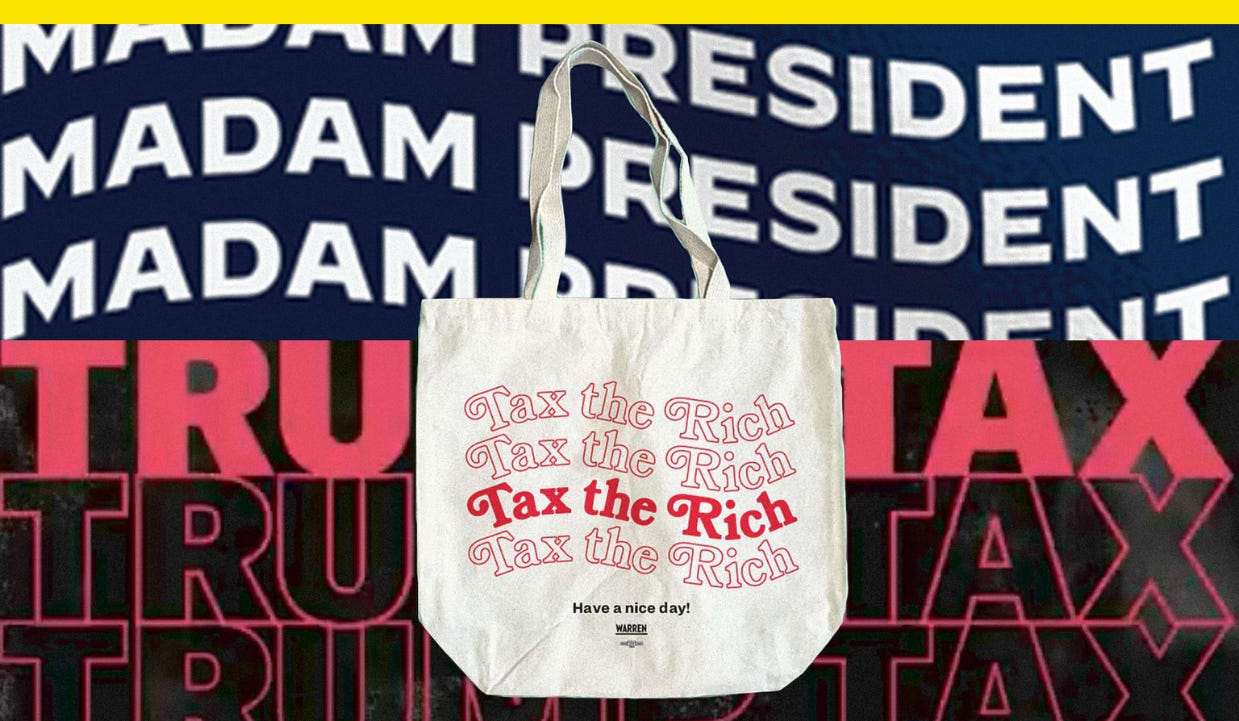

The words “Madam President” repeated six times and arranged to wave like a flag appear on a $32 hat, $32 tee, and $6 two-pack of stickers that Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign is selling. There’s a $32 “Pro Choice Voter” tee being sold by Ruben Gallego, the Democratic congressman from Arizona running for U.S. Senate. And Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) makes a Brady Bunch reference with her $55 “Marsha, Marsha, Marsha” crewneck, $25 tee, and $20 pizza cutter.

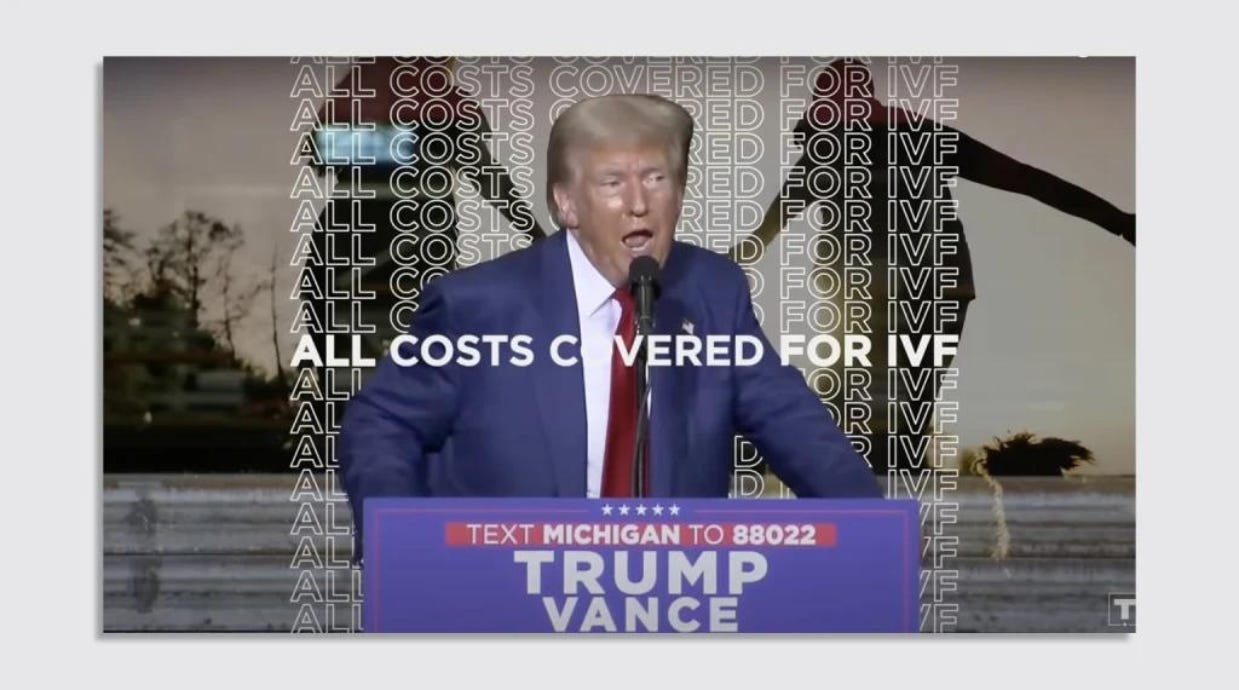

Repetitive, stacked type appears in ads as well. At a rally last month in Michigan, former President Donald Trump said if elected, his administration would mandate insurance companies pay for all costs associated with IVF treatment. To emphasize the point, in a new campaign ad, the phrase “All Costs Covered for IVF” is stacked 17 times.

Like Harris sharing that she’s a gun owner, Trump’s remarks were aimed at voters who might have concerns about his stance on an issue viewed by some as partisan. Senate Republicans voted against IVF protections twice in four months, but Trump supports IVF treatment, and his campaign is eager to tell you, spelling it out repeatedly on-screen so you’ll get the message even on mute.

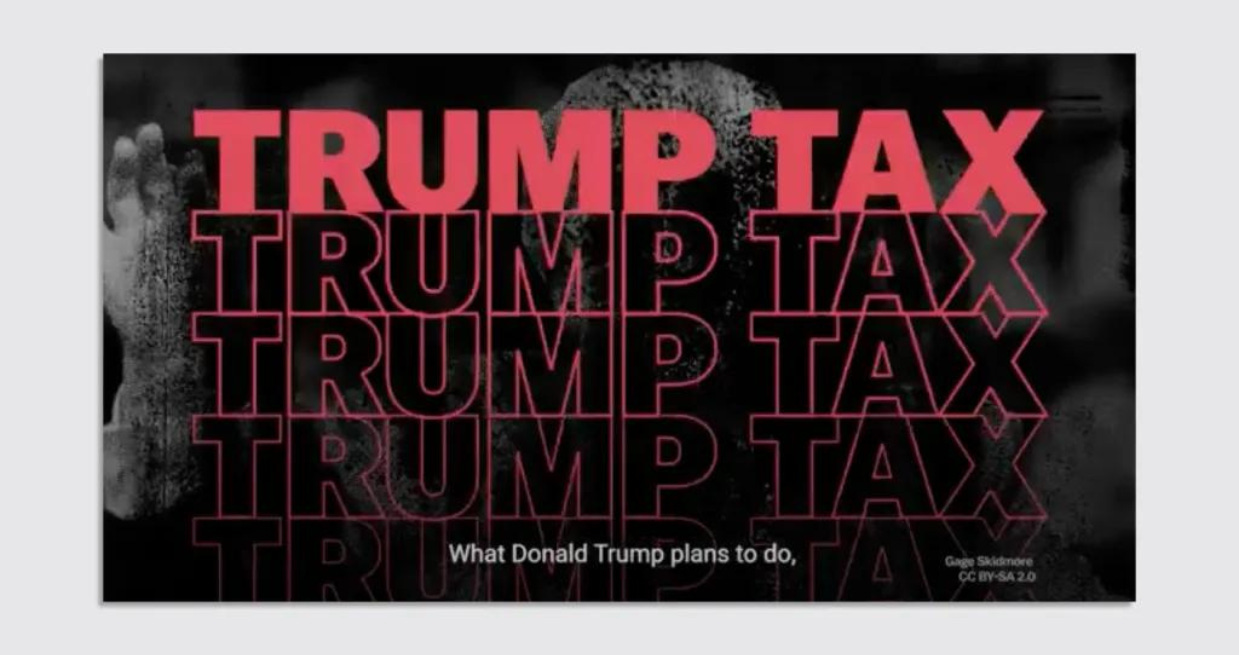

Stacked repeating text shows up as well in “Trump Tax,” a Harris campaign ad about the nickname she’s given to Trump’s proposed 10% tariff on foreign goods that economists say would raise prices and burden low- and middle-income consumers. Using audio from Harris’s August speech in North Carolina where she rolled out her economic policies, the ad says Trump would create “what is, in effect, a national sales tax.” The spot opens with the phrase “Trump Tax” flashing on the screen.

It’s a fun and engaging design style, but the stacked, repetitive-text approach also has a more tangible benefit. Because it takes up more space and repeats the same lines over and over again, it’s the visual equivalent of a candidate repeating a line multiple times in a speech — a graphic way to emphasize their point.

Politics in the front, pop culture in the back

Subscribe to my new free newsletter about politics, First Families, and pop culture:

The vice presidential debate made politics brand friendly again

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz and Sen. J.D. Vance (R-Ohio) are both Midwesterners running for the same job.

They’re also both fans of Diet Mountain Dew — making it the unofficial pop (that’s “soda” or “soft drink” for those outside the Midwest) of the vice presidential debate. And PepsiCo., its parent company, didn’t miss the opportunity to play into the news-making taste palettes of the candidates and advertise accordingly.

A pre-debate commercial showed security footage of a man delivering a cart full of Diet Mountain Dew backstage at the debate. When security tries to stop him, he says, “they asked for Diet Dew.” The brief 15-second ad ended with the message “VP Debate Starts Soon,” as if Mountain Dew was the spokesperson for the event itself.

At a time when many brands find current events too hot to touch, Diet Mountain Dew managed to insert itself into a political conversation in a way that was inclusive and not divisive, showing it’s still possible for brands to acknowledge news and politics in their advertising, while winking at its own 15 minutes of political fame.

“Many brands will want to advertise during debates because it’s obviously a high visibility event, but more strategically, it’s an opportunity to show neutrality — that their brand is for both sides and stands for something apolitical, a larger human truth or need that cuts across party lines,” says Dave Mayer, Senior Partner, Brand Strategy at global creative consultancy Lippincott.

The late 2010s saw brands speak out on social issues like equality, a trend that peaked in 2020 amid protests over racial justice following the death of George Floyd and amid the COVID-19 pandemic and a contentious presidential campaign. But brands have since experienced a marked depoliticization following conservative backlash and changing attitudes. A CNBC survey last year found 58% of Americans believe it’s inappropriate for companies to take a stand on issues compared to 32% who believe it is appropriate.

Diet Mountain Dew was lucky in that it didn’t have to take a stand on any issue of real cultural consequence in order to plug in to the current conversation around its product, making the move low-risk in terms of public perception, and potentially high reward in terms of engagement and brand lift. It was able to simply highlight its bipartisan appeal, which at least one politician has learned not to cross.

After Kentucky’s Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear demeaned the drink in July, he winkingly walked it back during a subsequent press briefing. “To Diet Mountain Dew, very sorry, didn’t mean to say negative things about you,” he later said, cleaning up his remarks to a few chuckles from reporters in the room.

Johnsonville, a Wisconsin sausage company, also aired an ad that referenced politics during the debate. The narrator of the 30-second “Townhall” suggested sausage may or may not be “the key to forming a more perfect union,” but either way, “it can’t hurt.” The ad blamed stale coffee and doughnut holes for our angry politics and put the swing state-based sausage brand at the heart of a diverse neighborhood block party.

The message of both ads was that food can bring people together, and that emphasis on unity mirrored comments from the candidates themselves, who spoke frequently during the debate about shared values and areas of agreement. For as divisive as politics seems today, that brands and political campaigns land on some of the same messaging shows they all see a public that’s thirsty for something to agree on.

Have you seen this?

Republicans are starting to raise alarms about Trump’s ground game. A person familiar with the outside effort to knock doors for Trump granted anonymity to speak candidly about their work, offered a counterpoint: “For those not seeing canvassers in traditional places the answer is, ‘No duh, we’re not running a traditional program.’” [Politico]

Tim Walz’ friendship bracelet won the vice presidential debate. Walz scored points in the accessories department — and with Swifties everywhere — thanks to the subtle presence of a Taylor Swift-style friendship bracelet under his shirt cuff. [GQ]

New Harris campaign ad seizes on the only viral VP debate moment. The Harris campaign launched its digital new ad, “JD Vance’s Damning Non-Answer,” across the seven battleground states on Wednesday aimed at attracting undecided voters. [The Daily Beast]

History of political design

Obama-Biden Texas flag bumper sticker (2008). This Texas-themed bumper sticker stuck the Obama O logo inside a star and was produced by Blue Texas Stuff, a merchandiser that put out other pro-Democratic items in the deeply Republican state during former President Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign.

Portions of this newsletter were first published in Fast Company.

Like what you see? Subscribe for more: