How should we fact check visual misinformation in the meme age?

Remember when the news images we saw were disseminated through gatekeepers, like newspapers and magazines? Publishers had editorial standards, so readers could trust that the images they saw were real. Photo illustrations were marked as such, and political cartoonists signed their names to their work.

The internet has blown that up.

Today, anyone can contribute their own images to the conversation, and while that’s democratized our visual rhetoric, it also opens up questions about how we contextualize and fact check visual information. It’s created some ~trust issues~.

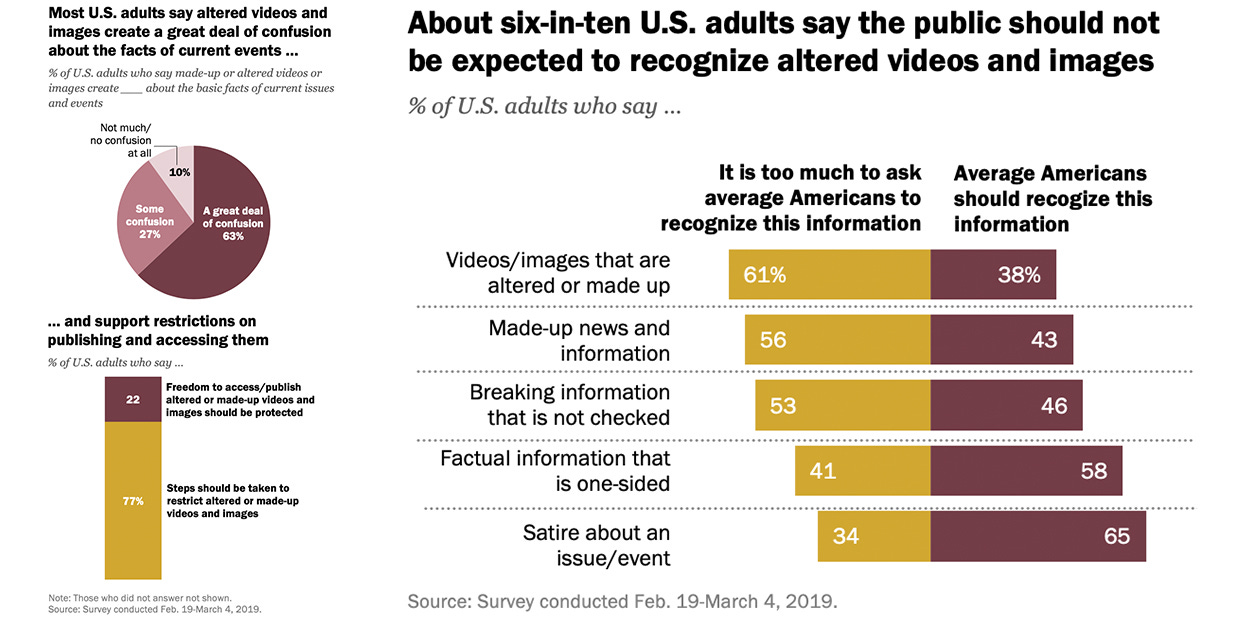

A June Pew poll found 90% of U.S. adults say altered videos and images create “some” or “a great deal” of confusion about the basic facts of current issues and events.

The poll also found 77% want steps to be taken to restrict altered or made-up videos and images, and 61% think it’s too much to ask the average American to recognize videos and images that are altered or made up.

Traditional visual standards in a digital world

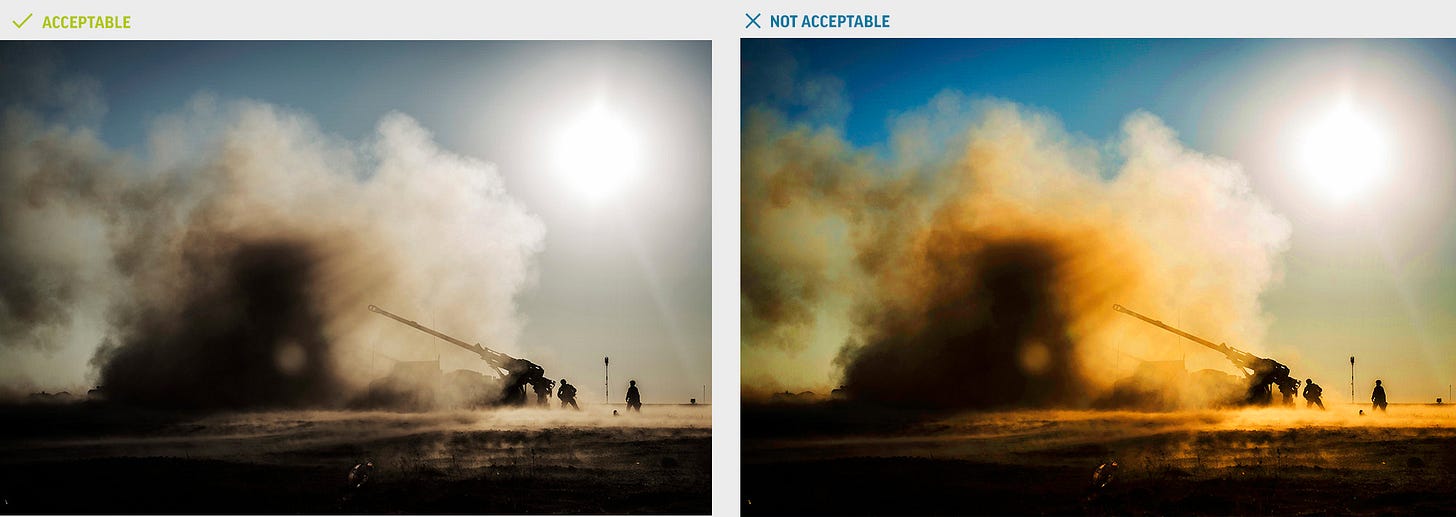

Something as simple as the filter you use on Instagram probably wouldn’t pass Associate Press standards. Per AP’s visual guidelines, it’s permissible for photographers to crop, convert to grayscale, make limited tone and color adjustments, and use tools to eliminate dust on camera sensors or scratches on scanned negatives, but not much else. They can’t even remove “red eye.”

Credit: Associated Press

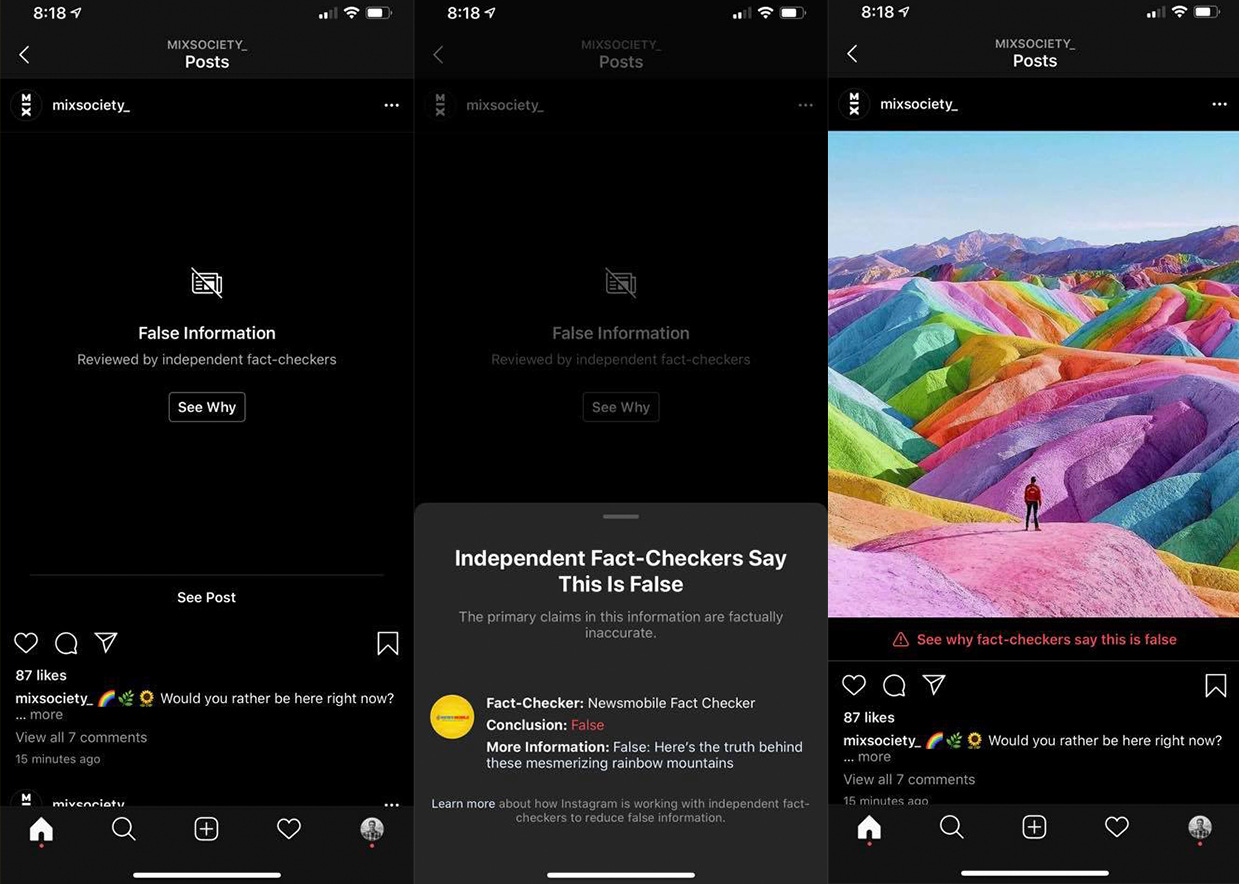

Obviously, not every image you see adheres to AP standards. Earlier this month, photographer and creative director Toby Harriman noticed an image in his feed that was marked with Facebook’s “False Information” warning. It was a shot of Death Valley National Park originally taken by photographer Christopher Hainey that had been Photoshopped into rainbow-colored mountains by designer Ramzy Masri.

The post has since been deleted, but here’s what it looked like, along with the fact-check warning Harriman saw, via his post about it on Facebook:

“Interesting to see this and curious if it’s a bit too far,” Harriman wrote about whether the limits imposed by Facebook’s “False Information” regulation were overly strict.

This rainbow mountain image has been fact checked before, by Snopes in 2017, and certainly wouldn’t meet AP’s standards. Because it was flagged, the image was filtered from Instagram’s Explore and hashtag pages.

Subscribe to Yello for the latest news on the culture, branding, and visual rhetoric of politics, delivered each week:

Following news coverage and criticism that art shouldn’t be held to the same standards as news — “Instagram’s decision to hide Photoshopped images is a disservice to art,” read a headline from The Next Web — Facebook said the independent fact-checker that had classified the image had removed the “False Information” label.

For now, social media platforms respond to edited media on a case-by-case basis. Their enforcement can be inconsistent (politicians are still allowed to lie in ads on Facebook!) and the various platforms are hardly on the same page.

Last year, video of Speaker Pelosi that was slowed down so it appeared she was slurring her words was removed from YouTube for violating its standards, while Facebook kept the video up but said it was trying to limit how far it spread.

Credit: via the Washington Post

Earlier this month, in another case of political image doctoring, Rep. Paul Gosar (R-Ariz.) tweeted out a Photoshopped image of former President Obama shaking hands with Iranian president Hassan Rouhani. Obama and Rouhani have never actually met, and the photo Gosar tweeted superimposed Rouhani’s face on an image of former Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who Obama met with in 2011. The image is still up on Twitter.

Gosar defended the post, tweeting “no one said this wasn’t photoshopped. No one said the president of Iran was dead. No one said Obama met with Rouhani in person.”

But nothing in his original tweet indicated it was fake, and as the aforementioned Pew poll found, Americans don’t think we should expect the average person to identify fake images.

President Trump is a prolific poster of Photoshopped images. As I wrote in December, a number of his top posts on Instagram in 2019 were memes that used altered photos. While images like Trump’s face superimposed over fictional boxer Rocky Balboa’s shirtless body are clearly fake, he doesn’t label them as edited.

How news outlets are responding

There are multiple attempts by news outlets and others to come up with some sort of standardized language to describe edited media. The Washington Post’s Fact Checker has come up with categories for describing altered video, for example. Here are their terms for manipulation:

Under these standards, the aforementioned Pelosi video would be categorized under “malicious transformation” as “doctored,” while something like “isolation” would be used for a video that was clipped so as to cut off context and present a false narrative.

Another attempt at standardizing the language to describe manipulated media is MediaReview, a proposed guide for how to describe altered images and videos. Under the MediaReview standards, which are still being drafted, images could be described as “authentic” if they’re presented accurately, while attempts to mislead could be labeled as “cropped,” “transformed” if elements are added or deleted, or “fabricated,” for completely false images that are made using AI, 3D software, or other means.

The News Provenance Project, a collaboration between the New York Times’ Research & Development group and IBM, has researched how context could travel with visual content. A proof-of-concept used blockchain to store metadata with a photo, and would provide readers with additional information when viewing photos, like the precise location, time, and date the photo was taken, the photographer who took it, as well as multiple photos that show different angles from the scene.

A News Provenance Project proof of concept shows a photo that includes additional information and photo angles.

This information could be especially useful for images that are authentic but posted with false information, like old photos of protests or natural disasters that resurface with new news events. This happened recently with the Amazon rainforest fires, with celebrities and others sharing photos that were either old or not taken in the Amazon.

For better or worse, social media has radically changed the way we share and consume news images and video. Visual misinformation travels at lightning speed, but correction to that misinformation moves at a snail’s pace. Developing the language to describe how media is altered or misleading, as well as giving news consumers the tools to clearly and easily see what’s real and what’s not could go a long way in a building healthier information ecosystem.