America could use some COVID memorial

Plus: The pandemic art that moved me most

Hello, in this issue we’ll look at why the U.S. needs to better acknowledge the COVID-19 pandemic and how memorials, art, and rituals can help us do that.

Scroll to the end to see: the irony in this year’s White House News Photographers Association Political Photo of the Year winner 📷

America could use some COVID memorial

On this day in 2020, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a pandemic. Five years later, at least 1.2 million Americans have died from COVID-19, a death toll higher than our Civil War, making the pandemic the deadliest event in U.S. history.

Beyond the empty chairs around the dinner tables of hundreds of thousands of American families, COVID-19 lowered our life expectancy, turned us into homebodies, made what now appears to be a permanent change to the way we work, and disrupted relationships, social lives, and career paths. It’s a scale of grief I don’t believe we’ve yet fully grappled with, but we should. The U.S. could benefit from memorializing the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We tell ourselves we’ve moved on and hardly talk about the disease or all the people who died or the way the trauma and tumult have transformed us,” David Wallace-Wells wrote in this excellent retrospective of how COVID-19 remade America. “But Covid changed everything around us.”

COVID-19 reordered our politics too, even if our politicians don’t talk about it anymore. Our rush to move past the pandemic can be noticed in the contents of our political ads. In mid-September 2020, COVID-19 was the focus of more than half of former President Joe Biden’s campaign ads, and later that fall, it was the No. 2 topic mentioned overall in both Biden’s and President Donald Trump’s ads, according to Wesleyan Media Project. When I asked last October how frequently COVID-19 was mentioned in 2024 campaign ads, a spokesperson for the Wesleyan Media Project told me it was mentioned in less than 1% of federal airings.

The past two presidential elections saw incumbents who underestimated the devastation and effects of the pandemic get booted from office. Trump called for then-President Barack Obama to resign after a single American doctor contracted Ebola in 2014 but didn’t follow the same advice himself during his botched, misinformed response to COVID-19. In 2020, Biden said someone whose presidency saw more than 220,000 COVID-19 deaths “should not remain as president of the United States of America.” After he took office, 750,000 more Americans died.

Biden claimed in his final State of the Union address last year that “the pandemic no longer controls our lives,” but Gallup polling at the time told another story. A 57% majority of U.S. adults said their life had not gotten back to “normal” since the pandemic, and as much as the 2024 race was about the economy, missing from the discussion was the pandemic’s role in all of it. Biden failed to draw a connection between the pandemic recession and the K-shaped recovery and inflation that followed. Only in the campaign’s closing weeks did Obama argue global inflation was “a legacy of the pandemic that wreaked havoc on supply chains” while speaking as a surrogate for former Vice President Kamala Harris.

One reason for our collective amnesia around the deadliest event in U.S. history, I believe, is the lack of compelling visuals. In a culture that communicates through images, an invisible enemy was all too easy to ignore, and unfortunately, one of the most defining elements of the pandemic, the face mask, didn’t end up as a unifying symbol of our collective efforts to defeat COVID-19 together, but rather a partisan symbol. When Trump speaks of his near-death experience, it’s always the more graphic example, the shooting, and never the time he was hospitalized with COVID-19. He was reportedly much sicker than he let on after testing positive for the virus, but to admit as much would have undercut his attempts to downplay it.

The visual language of pandemic grief and remembrance

Luckily, there are symbols that help visualize COVID memorial and grief, the white flag and the yellow heart. The white flag was used in artist Suzanne Brennan Firstenberg’s installation In America: Remember, and the yellow heart started as a symbol of pandemic grief in the U.K. before making its way to the U.S. Survivors have used these symbols to remember those we’ve lost, and I believe they are two of the most powerful tools we have to visualize the tragedy. For such a dark event, they invite lightness and hope.

When my father died from COVID-19 in February 2021, my initial reaction as a journalist was to call for memorials to those we lost. I felt then as I feel now that there would be efforts to erase those who died and minimize the pandemic’s cost, and that has come to pass. But memorials could make those losses more tangible and help us collectively heal.

“Rituals of mourning and remembrance help people come together and share in their grief so that they can return more clear-eyed to face daily life,” George Makari and Richard Friedman wrote last year in the Atlantic about the political ramifications of America’s unprocessed COVID grief. They argued “the country has not come together to sufficiently acknowledge the tragedy it endured,” and I agree.

Two of the most powerful experiences with COVID memorial I’ve experienced were art. In America: Remember, the public art exhibition on the National Mall, used small white flags to memorialize every American life lost to the virus, and it felt overwhelming to see the scope of the pandemic’s death toll, but it also made me feel less alone.

Artist Monica Aissa Martinez’ exhibition Nothing in Stasis was grounding. Dedicated to her father Roberto and brother Chacho, who both died of COVID, the exhibition showed portraits drawn in the style of anatomical illustrations and she didn’t leave out the cause of death of her family members. The small illustrations of the spiked virus in her portraits (above) made me feel seen. In a world that told me COVID was no big deal and that those who died were past their life expectancy, simply acknowledging COVID’s reality was powerful.

COVID-19 reshaped our lives in ways we can see and in ways we can’t, but our response to its memory remains incomplete. Grief without acknowledgment festers, and a country that refuses to remember cannot fully heal. Memorials — whether in the form of art, public spaces, or shared rituals — aren’t just about the past, they shape how we move forward. America could use some COVID memorial, now more than ever.

Previously in YELLO

Have you seen this?

The winner of the White House News Photographers Association Political Photo of the Year can’t cover the president now because he works for the Associated Press. The Trump administration has banned the AP over its refusal to follow Trump’s executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico, and AP photographer Evan Vucci, who photographed Trump after the shooting in Butler, Pa., shared this message after winning Photo of the Year:

Once declared “permanent,” Washington, D.C.’s Black Lives Matter Plaza will soon be painted over. D.C.’s mayor says the lettering will be replaced with art celebrating America’s 250th birthday. [Fast Company]

Trump turns the White House lawn into a Tesla showroom. Tesla delivered five of its vehicles to the White House and parked them on a driveway for Trump to personally inspect, hours after he said in a post on his app Truth Social that he planned to buy a Tesla to demonstrate his support for Musk and for the slumping car company. [NBC News]

History of political design

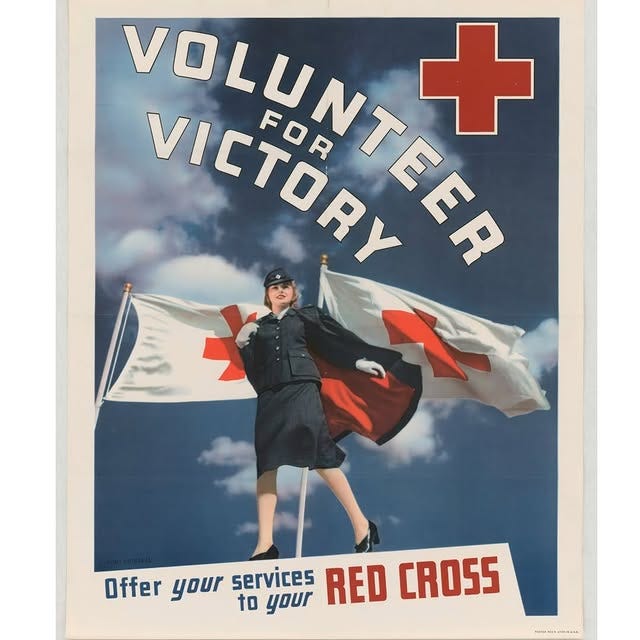

"Volunteer for Victory. Offer your services to your Red Cross" poster (ca. 1942-1945). This poster calling on Americans to come together and volunteer for the good of public health was shot by Toni Frissell, a photographer who worked for Vogue before she became the official photographer for the American Red Cross and the Women's Army Corps of the U.S. Office of War Information during World War II.

Like what you see? Subscribe for more:

How do we memorialize something our politicians and businesses have actively erased? When 1,000 Americans are still dying from COVID every week? When Americans with disabilities have increased 20% since 2020?